The EU’s AI Act has finally arrived, but what does it mean for the sector?

More than three years after the European Commission’s proposal to introduce the world’s first regulatory framework for AI, the EU AI Act is finally here. Adarga’s Chris Breaks explores the immediate impact of the EU AI Act, the obligations imposed by it, and the timelines for compliance.

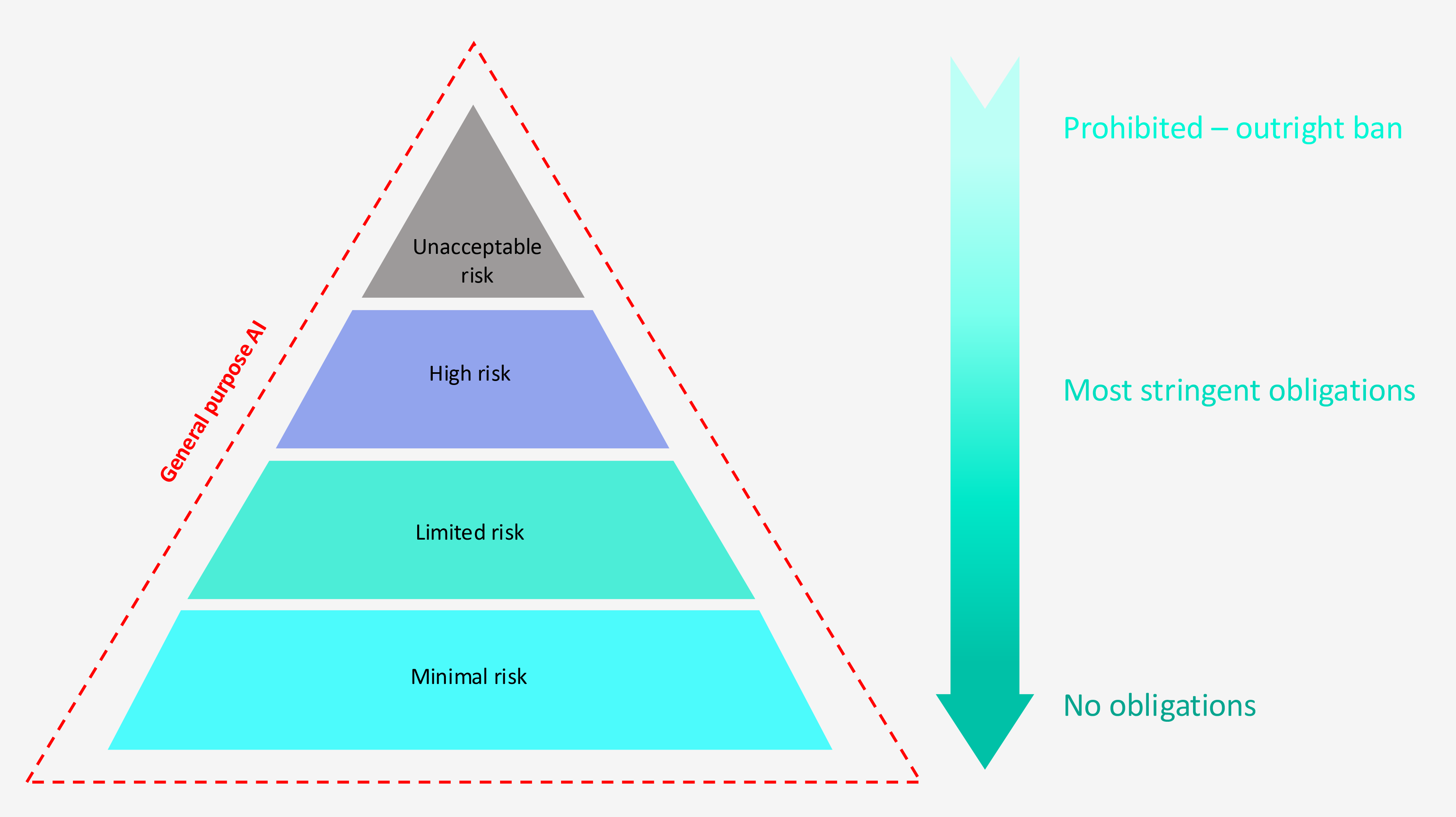

The AI Act adopts a risk-based approach to regulation by categorising AI systems[1] based on the potential risk they pose to health, safety, and fundamental rights. The obligations imposed are proportionate to the level of risk the AI system poses. Figure 1 below sets out each of the four risk-based categories of AI systems and their interaction with general purpose AI.

Figure 1. Risk-based categories of the EU AI Act

Starting from 1 August 2024, organisations must…

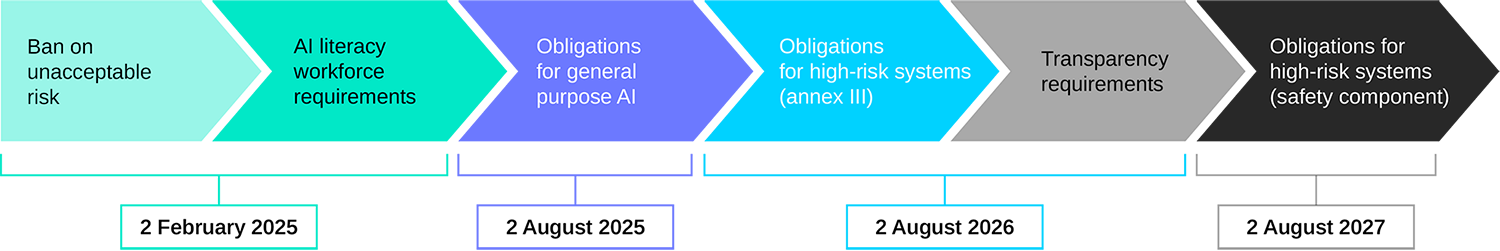

As with many other high-profile pieces of EU legislation (such as GDPR), the Act will be implemented in phases. While it was formally adopted on 1 August 2024, the majority of the Act’s obligations will not come into force until 2 August 2026, and it will not be until 2 August 2027 that the Act is fully implemented.

The phased approach to implementation means that AI systems that pose the greatest risk to fundamental rights and values will be addressed by the legislation first. AI systems that are deemed to pose an unacceptable level of risk will be banned outright from 2 February 2025.

Examples of prohibited AI systems include those that:

- employ subliminal techniques to manipulate a person’s behaviour;

- predict the likelihood of someone committing a crime based on profiling;

- ‘scrape’ in an untargeted manner facial images from the internet or CCTV to create facial recognition databases;

- infer a person’s emotions in the workplace or educational institutions;

- use real time remote biometric identification in public spaces for law enforcement purposes.

Although the ban on prohibited AI systems is not yet live, given the short deadline for compliance – six months from the Act taking effect – organisations currently developing or using systems that employ these techniques need to start assessing their risks and developing plans to address any areas of potential non-compliance now. Failure to do so could see organisations hit with fines of up to €35 million or 7% of global turnover – whichever is higher[2].

Does anything else kick in on 2 February 2025?

Short answer: Yes. In addition to an outright ban on prohibited AI systems, from 2 February 2025, providers and deployers of AI systems must also implement measures to ensure their staff have a sufficient level of AI literacy. AI literacy means equipping staff with the skills, knowledge, and understanding that enable informed decisions regarding AI systems. This includes awareness of opportunities, risks, and potential harms associated with AI. While there are no specific fines for failing to ensure AI literacy amongst a workforce, non-compliance will likely impact the extent of enforcement measures taken against organisations for other infringements.

And after 2 February 2025, the focus shifts to general purpose AI

One of the biggest challenges with regulating AI is the rapid evolution of the technology. The Act’s proposed regulation of general-purpose AI (GPAI) illustrates the difficulty of trying to regulate a moving target. GPAI is defined as an AI system that displays significant generality capable of competently performing a wide range of tasks. Following the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022 – the most well-known example of a GPAI system – EU regulators have been scrambling to agree how best to regulate these foundational models. Ever since the AI Act was first proposed back in 2021, regulation of GPAI has become a game of cat and mouse. Each time a new GPAI model was released, EU regulators were forced back to the drawing board – tweaking the Act’s draft provisions to try and prevent the EU’s landmark regulatory project from becoming outdated before the ink on the statute book had even dried. Time will tell on whether the EU has been successful in developing a long-term model to regulate GPAI.

For now, the Act distinguishes between three different types of GPAI based on the level of risk each poses and places stricter obligations on the higher risk systems: (1) GPAI with systemic risk; (2) standard GPAI; and (3) standard GPAI released under a free and open-source licence. Providers of GPAI with systemic risk have the largest number of obligations including (amongst other things) a requirement to publish the model on a public list, to perform model evaluation and adversarial testing, and to document and report any serious incidents to the AI Office. In addition, all providers of GPAI (regardless of type) are required to comply with copyright laws and publish details on the content used for training the

model.

These obligations take effect from 2 August 2025 – 12 months after the Act was adopted. The Commission may impose fines of up to €15 million or 3% of global turnover (whichever is higher), if providers of GPAI fail to comply with the relevant obligations of the Act.

Enter high-risk AI regulation

After 2 August 2025, the next stop in the Act’s risk-based approach to regulation is high-risk AI systems. The Act does not provide a single, overarching definition of high-risk AI systems. Instead, it outlines what constitutes high-risk based on the context in which the system is used and the potential impact of its application. An AI system will be deemed high-risk if it falls within one of two categories:

- If the AI system is a component in, or is itself, a product subject to existing EU product safety regulations listed in Annex I of the Act and the safety component is required to undergo a conformity assessment; or

- If the AI system is specifically classified as high-risk by reference to Annex III of the Act.

Examples of high-risk AI systems that fall within the category one definition include AI systems incorporated into EU regulated products such as toys, aviation, cars, medical devices, and industrial machinery. Meanwhile, AI systems deemed high-risk by virtue of being listed in Annex III include those used in critical infrastructure (such as supply of water, gas, and electricity), education and vocational training, employment and recruitment, and law enforcement systems.

Given the Act’s risk-based approach to regulation, short of an outright ban, high-risk AI systems are subject to the most stringent regulatory requirements. The extent that an organisation is required to meet these obligations is dependent on its role within the AI supply chain i.e. whether the organisation is a provider[3], deployer[4], importer[5], or distributor[6]. Providers of high-risk AI systems must (amongst other things):

- implement a risk management system to identify, evaluate, and mitigate risks to health, safety, or fundamental rights;

- carry out appropriate data governance and management practices for training, validating, and testing data sets to limit bias, discrimination, or inaccurate results;

- draft technical documentation to demonstrate compliance with the Act’s obligations and make it available to relevant authorities for compliance assessments;

- conduct automatic recording of events to ensure traceability of the system’s functioning;

- develop systems in such a way to ensure transparency to enable deployers to interpret output and use the system appropriately with instructions for use which confirms the identity and contact details of the provider, the characteristics, capabilities and limitations of the system, and human oversight measures to facilitate interpretation of output;

- develop AI systems with human oversight to help prevent or minimise risks to health, safety, or fundamental rights during use;

- ensure the AI system undergoes a conformity assessment before it’s placed on the market;

- register the AI system in an EU database.

Importers and distributers of high-risk AI systems are subject to more limited obligations such as a requirement to ensure the provider has complied with its own obligations under the Act e.g. it has carried out a relevant conformity assessment procedure and drawn up appropriate technical documentation for its system.

The date on which the above obligations enter into force depends on the category the high-risk AI system is assigned to. For AI systems specifically listed in Annex III of the Act (category two definition), the obligations will come into effect on 2 August 2026. For AI systems intended to be used as a safety component of a product or where the AI itself is a product and the product undergoes a conformity assessment (category one definition), the obligations will take effect on 2 August 2027.

Limited and minimal risk AI systems

At the base of the AI risk pyramid are limited risk systems, which only triggers transparency obligations; followed by minimal risk, which does not trigger any obligations whatsoever.

Limited risk AI systems are not specifically defined in the Act but are essentially AI systems that directly interact with people but do not pose a significant risk to health, safety, or fundamental rights. Examples include chatbots, systems that generate synthetic content (such as images, videos, text, or deepfakes) and emotion recognition systems. These limited risk AI systems are subject to the following transparency obligations, which take effect from 2 August 2026:

- providers must ensure individuals are informed when they are interacting with an AI system;

- providers of AI systems that generate synthetic audio, image, video, or text must ensure that such outputs are marked as artificially generated or manipulated;

- deployers of emotion recognition system or biometric categorisation must inform individuals that they are being exposed to an AI system;

- deployers of an AI system that generates deep fakes must disclose the fact that the content has been artificially generated or manipulated.

Finally, all other AI systems that do not fall into the prohibited, high-risk, or limited risk categories, will be designated as minimal (or “no”) risk AI systems. These AI systems are not subject to any regulation by the Act. The vast majority of AI systems will likely fall into this category. Typical examples include spam filters, recommender algorithms, and AI used in video games.

What should organisations be doing to prepare?

Figure 2. Key compliance deadlines

As discussed, the first set of substantive obligations introduced by the Act will not take effect until 2 February 2025. These will mostly apply to AI systems that pose an unacceptable level of risk. It is not until 2 August 2026 that the majority of obligations will then take effect. Despite this, organisations involved in the AI supply chain (be that as providers, deployers, distributors, or importers) should start taking steps now to ensure they are prepared for compliance. Early engagement will give these organisations more time to understand the requirements of the Act and its impact across their supply chains.

If you’re working in an organisation involved in an AI supply chain, these are some of the steps you should be taking now:

- One of the first steps to ensure readiness for compliance is to engage the right people in your organisation to assist in the preparation for and continued compliance with the Act. To ensure each department is properly represented, organisations should create AI working groups comprised of various stakeholders from across the organisation such as legal, risk, data privacy, data science, product, and engineering. At Adarga, our Committee for Responsible AI, ACRAI, is comprised of stakeholders from across our business. When it comes to understanding the ethical and legal implications of our AI, this cross functional group ensures the opinions and experiences from a wide range of people are considered.

- Organisations should categorise the AI systems in their supply chains according to the Act’s risk categories. If any prohibited AI systems are identified, organisations should urgently take steps to ensure compliance (e.g. by removing the prohibited system) or mitigate any potential issues (e.g. assessments to establish risk of non-compliance) given these systems will be banned from 2 February 2025.

- Once AI systems have been appropriately categorised based on risk, a gap analysis against the Act should be carried out by the AI working group to identify areas of potential non-compliance. An action plan should then be put in place to address these gaps. Relevant deadlines should be considered when addressing gaps to ensure the most pressing issues are tackled first.

- If appropriate, consider communicating with external stakeholders, such as customers, suppliers, and partners, to understand the steps they are taking or plan to take to ensure compliance. At Adarga, we are already seeing more of our customers and suppliers asking questions and looking to discuss their expectations and requirements around compliance with the Act, both for themselves and their partners.

- With the Act’s focus on documentation and record keeping, ensure your organisation has in place comprehensive document management systems that meet the requirements of the Act and ensure documents are appropriate for regulatory authorities should they ever request to view them.

- Ensure staff are properly and regularly trained on relevant legal, regulatory, and ethical considerations regarding the AI systems deployed in the supply chain.

- Internal and customer-facing terms and conditions and related policies should be updated and reviewed periodically to ensure continued compliance.